Robin Carpenter Goes Big with his Gravel Debut

“The first five hours of Unbound were similar to any one-day race I’ve done in Europe,” Robin Carpenter says. “And then we kept riding—and riding hard—for another five hours.” New pursuits challenge anyone, of course, but when your normal pursuit means racing a bicycle at the highest level in the world, a rough doubling of that effort would surprise anyone. Robin Carpenter rides for Rally Cycling, the most successful domestic pro cycling team here in the United States, and on June 5th he intended to be in Northern France, at the strangely named Quatre Jours de Dunkerque (“four days of Dunkirk,” strange because it’s normally raced over six days). The COVID-19 pandemic cancelled that event in 2021, and Carpenter found himself stateside in late April with fitness to spare and an empty weekend. Just getting into Unbound, of course, posed a challenge, and a friend went to work trying to transfer his entry to Carpenter. That endeavor took until May 20th, so Carpenter knew he would race with only two weeks to spare. “I’d be getting ready anyway,” he says. “Doing my research, trying different hydration packs. I only went on one really big ride: a 150-mile round trip of Mauna Loa on the Big Island in Hawaii. It was hot, hard, and humid, and my numbers were pretty good. I was pleased with that.”

Carpenter, to anyone who follows cycling in the United States, is a well-known name. He’s been on the podium twice at our national road championships. He’s won or placed at many of the big races on this side of the Atlantic. Since 2014 (when he graduated from the prestigious liberal arts college Swarthmore after only seven semesters) he’s also raced in Europe, slowly building a portfolio of results and experience. Up until June 5th, 2021, however, none of those palmares included a gravel race of any kind. “I picked the brains of everyone I knew who had done the event,” he says. “I know Lachlan Morton from way back on our Garmin Development Squad days, and Alex Howes from just riding around. Lachlan’s advice was to baby the bike as much as possible, treat it more like a road bike than a mountain bike, and try to avoid slamming it into the sharp sections of gravel. Obviously avoiding flats and mechanicals is important, but he stressed that if you can stay clean in the first half of the race, you’re more likely to make the front group in the second half of the race, which is more or less what happened.”

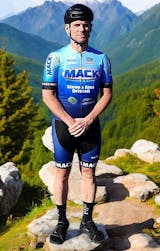

Cool, calm, and collected. @RobinmCarpenter filling bottles and tires at the feed zone 👊🏽

— Rally Cycling (@Rally_Cycling) June 5, 2021

Currently chasing leaders heading into the final hour of racing. Top 10 within reach!

🎥 Brian Co#UnboundGravel #Unbound pic.twitter.com/EUp1zYaIUz

A Hard Start

“We raced the start so much harder than I thought we would,” Carpenter recalls. Accustomed to hard starts in Europe, he took it philosophically and treated the early selections as small tests. As he passed each test he’d tell himself “OK, that was awesome, nice work, you passed that one,” but the pace surprised him. The lead group would drop some riders at each selection and then...just keep riding hard. Carpenter asked himself why the pace was staying high when he knew the gap would stay open even at fifty watts lower. “I realized just how seriously the gravel pros take this race, and that’s something I’ll remember for next time. They do not mess around, and this is obviously how they make their living.” Carpenter survived the first 65 miles in the lead group, arriving at Aid Station One with the rest of the contenders. The aid stations at Unbound Gravel, for those who haven’t had the pleasure, occupy whole towns in the Kansas countryside. Rather than a stretch of ten-by-ten tents and a handful of volunteers, whole sections of each aid station town are designated as different zones, and riders are assigned to certain zones. The end result is one of impressive, nearly overwhelming chaos. Support crews shout for their riders, almost inaudible over the shaking cowbells and the whining vuvuzelas. Toss in early-race nerves without the late-race fatigue, and you have the recipe for a few pit area mishaps. Carpenter rolled up to his mechanic and began switching out his hydration pack, thinking that his mechanic had the bike in hand. His mechanic, on the other hand, thought Carpenter had the bike so he could lube the chain. The bike toppled over, cracking the hood clamp to one of Carpenter’s shifters. “We worked on it for about 40 seconds,” he recalls, “but the leaders were in and out of there in less than a minute, and we didn’t have the time to fix it. That was probably my low point: realizing I wouldn’t be able to be on the hoods for the rest of the day, plus having to get back to the leaders after leaving the aid station.” No stranger to long, difficult chases, Carpenter got to work. He could see the leaders up the road, moving up a long grade just outside of town. He put in a strong ten-minute solo effort and bridged the gap, rejoining the group around the 70-mile mark.

The Selection

Just as it did two years ago when the Unbound course headed north, the rough, shattered section of ranch land about 100 miles into the race provided the final selection of riders, and Carpenter was there to watch it. “Little Egypt” is a series of ravines, criss-crossed by trails that someone decided were roads. The section is littered with the aspirations of riders at this event, and culminates in a steep, loose section pockmarked by sharp rocks. “I was riding the downhills with a little more speed, maybe,” Carpenter remembers, “but when we climbed out Pete [Stetina] attacked and I lost contact. I knew I couldn’t go as deep as their effort would require, so I managed it as best I could, hoping I’d be able to get back on at the top. But when they went over the top they got together right away and started to work. I could tell they were basically trying to get rid of guys like me.” After getting dropped, Carpenter settled into a gravel experience most of us are familiar with: racing one’s self and avoiding mishaps. He did eventually flat, around the 115-mile mark, and spent about eight minutes fixing the issue, rejoining the second group on the road when they came past. “I knew that I’d be racing myself after around 100 miles, so I mostly focused on being my best and not giving up. You know everyone is going to have some problems, so when my CO2 inflator exploded I just tried to be patient, maintain a good attitude, and not freak out.”

The Finish

Carpenter returned to Emporia in a depleted group of three: the mountain bike great Jeremiah Bishop and Dutch road cyclist Dennis Van Winden. Carpenter probed his riding partners for their sprinting appetite, with Bishop suggesting rock, paper, scissors to decide it, and Van Winden offering stoic European silence. “I opened up the sprint a long way out,” Carpenter says. “Probably around 300 meters, actually, and I was happy to hold it and win my little group.” Following the race, there was little time for recovery—Carpenter and his wife (a decorated geneticist) were moving across the country from San Diego to Boston, where she’ll start a research fellowship at Harvard Medical School (the couple doesn’t lack for star power on either side of the partnership). When I reached him on the phone, he was taking a break from moving boxes into a large panel truck outside their California home. “I’m definitely not doing what I should be after a race like that,” he says. “But we’re moving after road nationals on June 18th and that’ll take the rest of the month. Then it’s back to training and I’ll probably head to BWR [the Belgian Waffle Ride] in the middle of July, depending on what’s happening with the team.” I asked Carpenter if he’d return to Unbound, to which he offered an enthusiastic yes. Ever the successful bike racer, he began unpacking his plans for the next Unbound, only 360 days away. “I think my fitness was where it needed to be,” he says. “My regular training gives me the volume and intensity I need for that race, so I think next time I’ll focus more on equipment and tire pressures and staying quick with less stress. I think I wasted a lot of energy ensuring that I stayed at the front of the group, and I think that cost me when the final selection was made. But mostly I was happy to see a lot of faces I haven’t seen in a while, both because of the pandemic and because racing in Europe is like going to another planet. It made me feel really good to see all those people, and yeah—I’d like to do that again.”